Sunswift II’s road to fame began with an angry phone call.

The year was 1998. The World Solar Challenge (WSC) originally scheduled to be held in October was just cancelled. John Ransom, Sunswift’s second Project Manager, was devastated.

“I was just working 7 days a week,” says John, recalling the preparation the Sunswift II team had completed leading up to the WSC. “I was working from 10 o’clock in the morning to 3 or 4 the next morning. I basically dropped out of civil engineering.”

After the Darwin-to-Adelaide solar race was cancelled, the team was in uproar. Many students had made plans to work or study after the 1998 WSC was supposed to have finished. “They really put a lot of people at a loose end,” says John.

He then decided to call Hans Tholstrup, the founder of the WSC. “I was crying to him about how it was. I was very angry,” he continues. “I might have said a few things to some people that with a bit of maturity and years behind me I regret.”

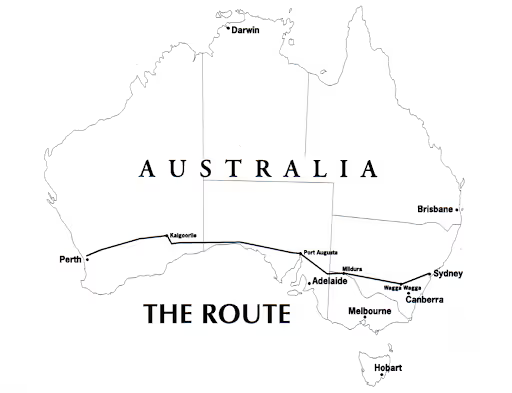

Tholstrup recommended John to attempt the Transcontinental Record from Perth to Sydney, timing the drive to occur during Christmas and the New Year when news cycles were slow. The Transcontinental Record from Perth to Sydney was set by Dick Smith in 1994, who had travelled approximately 4000km across the country within 8.5 days at an average speed of 60km/hr.

Kaylene Askew, then Executive Project Manager of Sunswift, says it was the right decision to take on the Record. “I think everyone felt that was a pretty good move from a media perspective since it was the only car in the race.”

Indeed, the attempt generated $2.4 million worth of publicity. “We had 3 helicopters following the car,” John recalls. “We were on every news channel.” The ABC made a documentary on them, with a film crew following their journey for weeks. TV Asahi, a Japanese television network, met up with them in South Australia for a day. NRMA and Toyota were prime sponsors of the attempt.

“I got my 15 minutes of fame,” he laughs.

However, Sunswift II failed to break the record after they were set back by five days of bad weather, meeting thunder, rain and dust storms. Shane Stone, Sunswift II’s Chief Engineer and Race Strategist, remembers “the great downpour” with amusement.

“We were basically out of battery at one third of the trip and limping for a good couple of days,” says Shane. Relying on the Nullarbor Plain’s flat land, the drivers altered their race strategy with their new goal now to get home safe.

“When you have extremely flat land, you can actually see these bright stripes across the road,” Shane explains. The drivers then paced the car to keep it driving at a constant speed in time with these stripes, hopping from one to the other.

At one stage, the canopy of the car blew off completely from the weather. Team members had to brave the weather and search for it, according to Kaylene.

The all-female driving team eventually crossed the finish line at the Sydney Opera House where Dick Smith, Tholstrup and police escorts were waiting. Sunswift II was only two days out from beating the record, travelling at a top speed of 70km/hr.

It was only a few days before Sunswift II entered another race: the Sydney-to-Melbourne CitiPower SunRace.

But first, we need to go back to the beginning.

A New Beginning

After John took up the reins of Sunswift II, the Project Manager came up with a bold new vision: to build their own solar car from scratch. Sunswift I, although “a beautiful car”, had been purchased second-hand from the Aurora Vehicle Association in 1996.

“We don’t want to just race Aurora’s car, as good as it is,” says John. “We’re here to try and build our own car."

“Even if we come last, we’d rather come last in our own car than win in a car we’ve picked up from someone else and driven away.”

John’s vision for the design of this new car came from his other passion: motorcycling. The inside of Sunswift II was lovingly modelled on a Ducati 916 motorbike and the chromoly space frame chassis had an Öhlins suspension, painted gold.

It also used Michelin ultra-low rolling resistance radial tyres, regenerative rear brakes, lithium ion batteries and a CSIRO 3kW electric wheel motor. The solar array was made up of BP Saturn solar cells.

The university’s support did not come easily at first. “We sort of forced the university into supporting us,” says John. “It was either you’re going to support us and we’re going to be a professional outfit, or we’re going to bring great embarrassment to you.

“Whether we’re doing it on a shoestring budget or we’re a laughingstock or we’re one of the best teams.”

The Evolution of Sunswift II

Sunswift II’s first prototype was never raced but underwent significant testing with the lamination process, using epoxy-fibreglass lamination on both sides of the cells.

The second version went on to complete the Transcontinental Record attempt, using the same lamination process. Its solar array suffered from some delamination during the attempt. Despite this, the team persisted in using the car to drive 1790km in the CitiPower Sunrace just a few days later.

The rules of the SunRace forced them to swap their lithium ion batteries for a 100kg lead acid battery, which, combined with the “subjective” penalties they received (one for passing notes between cars), led them to come third out of five entries after five continuous weeks on the road.

John then left the team, going on to compete in solar races in the US. His position was taken up by Chris Tucker and Sunswift II’s lifespan continued.

For using the CSIRO wheel motor, Sunswift II was requested by the Federal government to participate in a trade exhibition in Taipei, Taiwan in 1999. Sunswift 2.3 was built by way of repairing the damage to the solar array that occurred during transit.

This version went on to race in the eagerly-awaited 1999 World Solar Challenge. Its solar array consisted of BP Saturn cells, cut and shingled to prevent loss from busbar shading. The cells were then sprayed with Conformal Coating.

Sunswift 2.3 also competed in the 2000 SunRace. However, the vehicle’s solar array was irreparably damaged after it crashed into a Give Way sign as it swerved to avoid hitting the car that was braking in front of it.

“It was pretty scary, because these things are prototype cars,” says Shane. “You can design for it, but not like a regular road car that’s been tested in a crash.”

And it was after this event that Sunswift’s final incarnation came to life.

The TopCell Project

Sunswift is known for being the first and only solar racing team to have made their own solar cells. Sunswift II’s TopCell Project was the brainchild of this endeavour.

Under this project, the team worked with silicon wafer supplier Topsil to manufacture buried contact cells to construct a new solar array in preparation for the 2001 WSC. The team ended up making over 4000 solar cells.

Meanwhile, the team was also developing an innovative cell encapsulation technique which allowed the solar panels to mould to the curved shape of the car and minimise aerodynamic drag.

This project involved constructing a mould that could withstand the pressure from the lamination technique and creating a telemetry system that monitored the temperature of the process. One prototype of the encapsulation technique involved a solid steel beer keg, which was used to conduct a scaled-down vacuum testing of the lamination process. The solar array that emerged from this venture (after multiple test-runs) generated 1350W.

Sunswift 2.4 went on to race in the SunRace again in 2002 and 2003, coming an impressive 2ndin both.

Unfortunately, however, the car suffered severe damage after its trailer jack-knifed on the way to the WSC 2003, which wrote them off competing in the race that year.

Despite Sunswift II’s sudden end, the hard work that went into Sunswift’s very first self-built car did not go to waste – parts of Sunswift II were re-used in later models. “When Sunswift III beat the Transcontinental Record, I went down to have a look,” says John. “They had the wheel motor that we built. I was really proud of it.”

Related Achievements

World Solar Challenge '99

NRMA Sunswift II finished a respectable 18th out of 48 international entries.

Transcontinental Record Attempt '99

The car 'NRMA Sunswift II' completed 4,012 kilometres (2,493 mi) in ten days, despite five days of bad weather. Even though the record of 8½ days was not broken, the attempt was still regarded to be a success with $2.4 million worth of publicity generated.

CitiPower SunRace '99

Three days after completing the Perth-Sydney record attempt the team entered the CitiPower SunRace. NRMA Sunswift II obtained third place in a highly competitive field of five entries, proving the car's reliability and the team's dedication after five continuous weeks on the road.

Federal Government

NRMA Sunswift II participated in a trade exhibition in Taipei, on request from the Federal Government.

World Solar Challenge '01

UNSW Sunswift II was the 11th car to cross the line.

SunRace '02

2nd Place.

SunRace '03

2nd Place.