Since its founding in 1996, Sunswift has travelled almost 25,000 km across the Australian continent powered by sunlight. Now we go back in time to see just how far Sunswift has come from its humble beginnings right here at UNSW.

Like any other fourth-year engineering student faced with the prospect of choosing their thesis topic, Sunswift founder Byron Kennedy decided to go to the uni bar.

None of the prescribed topics interested him – they were all much too theoretical, in his opinion. He wanted to do something, build something. And after talking about it with a group of friends, an idea formed, nebulous, uncertain, crazy.

“I went to one of the professors at the time…and said we want to build a solar car,” Byron recalls.

Now three world records, seven different cars and hundreds of students, academics and alumni later, Sunswift has made a name for itself not only as the darling of UNSW’s Engineering faculty, but also a leader of solar energy development and innovation.

Professor John Storey, Chief Scientist of the Bridgestone World Solar Challenge (BWSC) Officials team and one of the first academics whom Byron approached, had leapt at the idea of creating a solar car racing team at UNSW. He himself had tried and failed to secure university funding to participate in the World Solar Challenge (WSC), the precursor to the BWSC, in the 80s and early 90s.

“Byron came into my office and said that he wanted to start a UNSW team. I was absolutely delighted,” says John. “I do remember he was really enthusiastic, really positive, and we chatted about what was going to be required.”

“I probably sounded a bit negative about his chances of success given the fact that I hadn’t succeeded in getting the university on board.”

As to why UNSW approved Byron’s proposal rather than John’s, Sunswift’s founder put it down to luck and support from the right people, and that the university was perhaps more eager to support a student-led endeavour.

And it just snowballed from there. A group of three quickly became a team of almost 30 other students and academics, with people coming from electronics, mechanics, biomedical engineering, design, finance, marketing, and more. 16 of them went on to compete in the 1996 World Solar Challenge. But first, they needed a car.

The Car

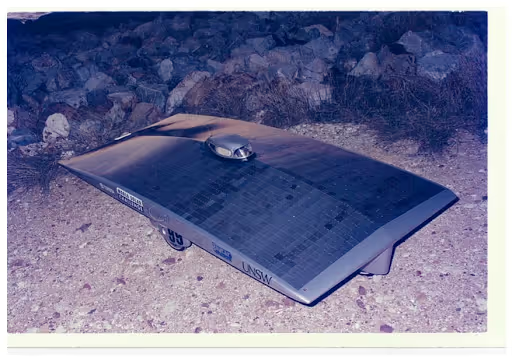

Sunswift’s first car came from a deal between UNSW’s photovoltaics department and the Aurora Vehicle Association, who gave the department a solar car that came fifth in the 1993 WSC in exchange for some cells.

“It wasn’t in too good a condition,” says Byron. “We had to replace all of the chassis - it had cracks and stuff in it by the time we got it. It was a fairly big overhaul.”

By “big overhaul”, Byron meant putting in a new motor, an electronic controller, tweaking up the solar array, replacing the battery and adding a GPS, which was an all-new technology at the time. In fact, three students from the School of Geomatic Engineering had travelled the entire route of the WSC before the actual competition in order to survey the vertical profile of the Stuart Highway. This information allowed the Sunswift team to strategise their own drive later in the year.

Byron says that the GPS technology they used was very advanced for its time. The surveying team used a Differential Global Positioning System (DGPS) to record and analyse the designated route for the race, which, unlike the more common Global Positioning System, a DGPS utilises two receivers to more accurately pinpoint its location. This means that the DGPS can take measurements accurate to 10cm, while the GPS on its own totals only 15m. The project ended up using 9 GPS receivers in total, which was worth $200,000 at the time.

The Sunswift car was also fitted with one of the most efficient solar cells at the time, manufactured right here at the Photovoltaic Special Research Centre in UNSW. Its solar array was rated as one of the best in the race, with a solar cell efficiency of 18.5 per cent. These cells, which had been adapted specially for solar vehicles in response to the increased manufacture of solar cars, have long been used by other solar car racing teams. It was only proper for Sunswift to take advantage of the university’s cutting-edge technology too. All-in-all, Sunswift I ran on approximately 1160 watts of power, the equivalent of a hair dryer.

The modifications to the chassis, various safety improvements and the installation of a larger assemblage of batteries than what was used by Aurora also meant that Sunswift I was the heaviest car out of all 46 solar vehicles in the WSC.

Despite the level of sophistication required in the engineering of this car, Sunswift always has been a student project, according to John. “I never had any input into any of the design or the changes to the car, and I think they rather liked it that way too,” he says. “They had their own ideas, and they did it their way.”

The World Solar Challenge

About 15 months later in October 1996, Sunswift I was ready for the road. The team was now finally able to meet their original goal of competing in one of the world’s premier solar car racing competitions: The WSC.

The WSC, held tri-annually for cars with solar-charged batteries, invited competitors throughout the globe to race across Australia’s scorching outback from Darwin to Adelaide. It was founded by two Australians, Hans Tholstrup and Larry Perkins, who had driven across the continent in their own self-built solar car. Competitors at the time included not only other national and international universities, but also corporate big names such as Honda and General Motors.

In his foreword to Speed of Light, a book dedicated to the 1996 WSC, David Roche wrote that solar car racing was valuable to racers in so many ways. It provided a statement of making progress in the field of ecology, provided a key tool in learning the technicalities of solar engineering, and was an invaluable opportunity for teams, particularly student-teams, to obtain project-management and leadership skills.

Now, with five support vehicles (two of which were sponsored by Toyota) and a core team of 16, which included an all-female driver team, Sunswift started the long haul from Sydney to Darwin as a test drive before the race in the Northern Territory – about 3000km in two weeks.

Byron says that the all-female driver team was chosen specifically to be gender-inclusive, saying that it “brought a nice amount of balance to the team.” The women came from different areas of university, including aerospace engineering, textiles and marketing. Byron says that there was also evidence that females were better at handling the hot track conditions and are generally lighter.

As with every race, there were a few (kangaroo-shaped) bumps on the road. The first accident occurred when the axle snapped and the car went sideways across the road before coming to a stop by a tree. Though the driver was unhurt, this accident set them back considerably as they were forced to travel at a reduced speed for the rest of the day, compounded by their loss of the car’s front wheels along the way.

Following that, a support vehicle provided by Toyota also suffered a hit. “The Prado was pulling the trailer and hit a kangaroo one night, as happens on those sorts of races,” says Byron. But the accidents didn’t end there.

“The trailer was then pulled by another smaller ute and it did a jack-knife, and I can’t even remember what happened there,” Byron laughs.

John Ransom, a team member of Sunswift I, admits that although they were funny at the time, the accidents had been extremely dangerous. “It’s actually frightening what happened. We’re lucky no one got killed, to be honest,” he says.

Nevertheless, a couple of brake failures, some tyre issues (which were resolved with the lucky help of a passing German cyclist) and a second axle breakage at the finish line later, Sunswift came a formidable 9th place after seven full days on the road.

On top of Sunswift’s above average performance in its first-ever race, this result and the process it took to get there contributed greatly to the early research of solar vehicles, photovoltaics technologies, the WSC and, most importantly, laid a foundation for the future of Sunswift.

From its humble beginnings at the campus uni bar, Sunswift has now become an organisation whose impact is felt across the country and shaped the lives of hundreds of students, scientists and engineers in the field, to which Byron adamantly attests.

“Sunswift is the best thing I’ve ever done,” he says. “The friendships you make last for a lifetime.”

Related Achievements

World Solar Challenge '96

Sunswift finished 9th out of 46 entries. This was the University's first entry in a solar car event amongst the prestigious and competitive entries from Honda Motors Corporation, the Swiss entry from Biel, and Mitsubishi Materials Corporation.